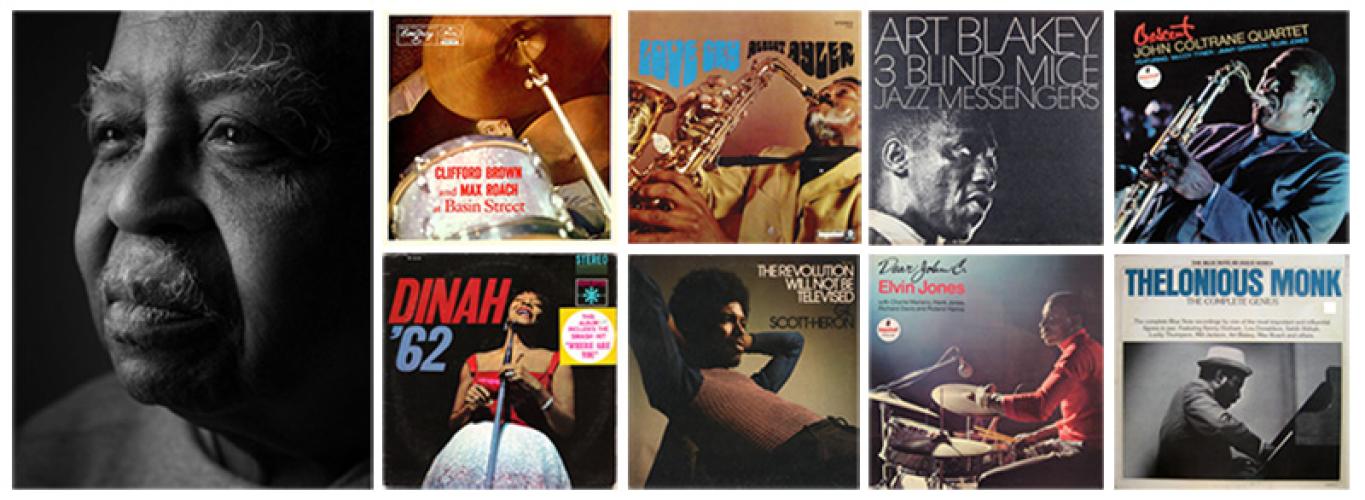

Chuck Stewart's Legendary Photographs (1927-2017)

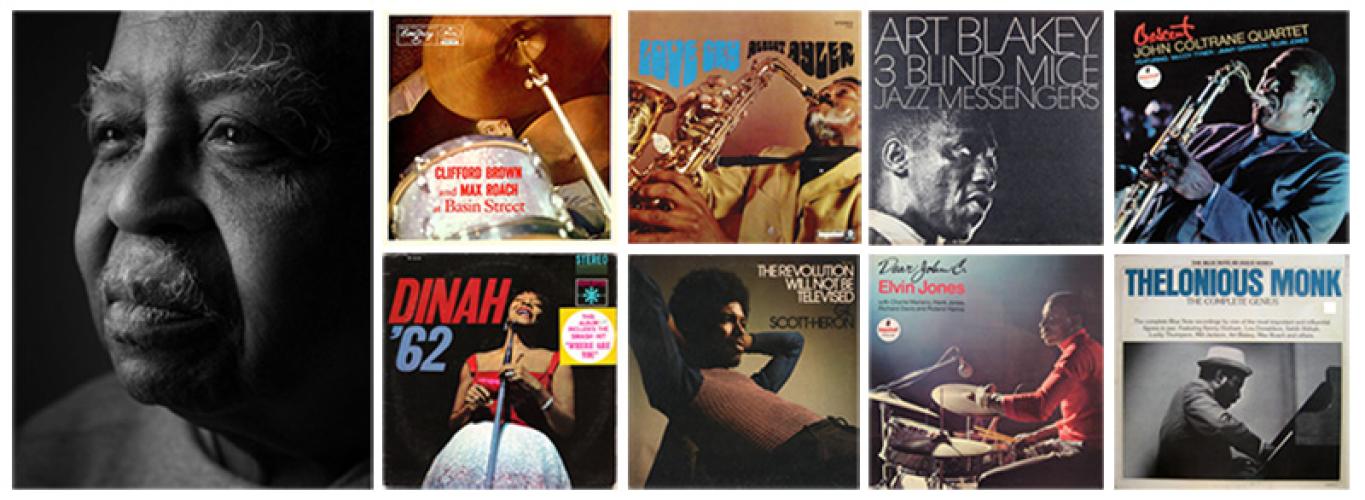

Chuck Stewart’s photographs, splashed across 2000+ record covers and spanning more than 70 years, helped define the look and feel of jazz as it burst forth into the listening imagination of the American public from the 1950s onward. His eye and his images have been a recognized force within the music world for generations, but only recently has Stewart’s name begun to creep into the cultural consciousness, making headlines for his long-overlooked photographs of John Coltrane, Max Roach, and James Brown, among others. This OHIO alumnus (B.F.A., 1949) has a fascinating story winding through the history of jazz, photography, and the atom bomb.

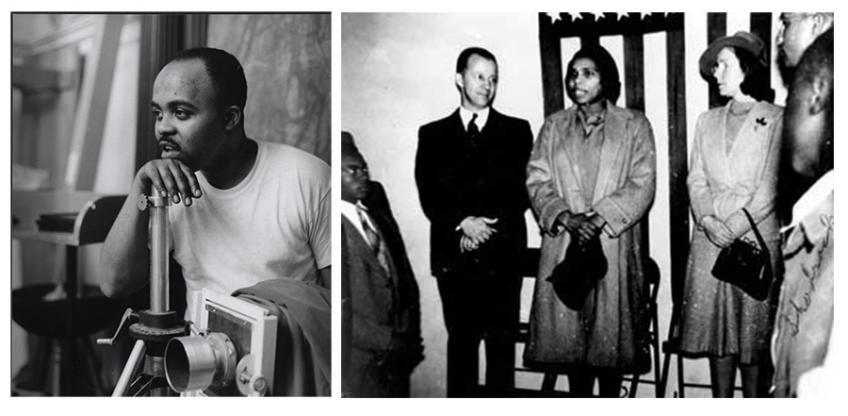

Born in Henrietta, Texas in 1927, Stewart grew up in Tucson, Arizona. Using a Kodak Brownie Six-16 camera his mother gave him, Stewart captured renowned contralto opera singer Marian Anderson on film while she visited his school. Many of his friends and classmates wanted copies of his pictures, and this experience galvanized 13-year-old Stewart’s interest in the power of the camera and the photograph.

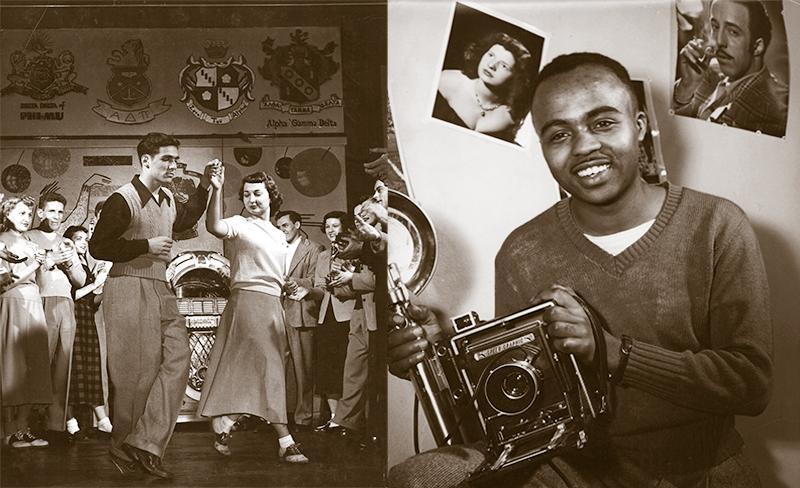

From 1945 to 1949, Stewart attended Ohio University; at the time it was the only collegiate level degree granting photography program in the country that would accept black students.

Stewart would have spent an extraordinary amount of time working in the Hall of Fine Arts, an ivy-covered building with a basement outfitted with the darkroom and equipment of the department of photography.

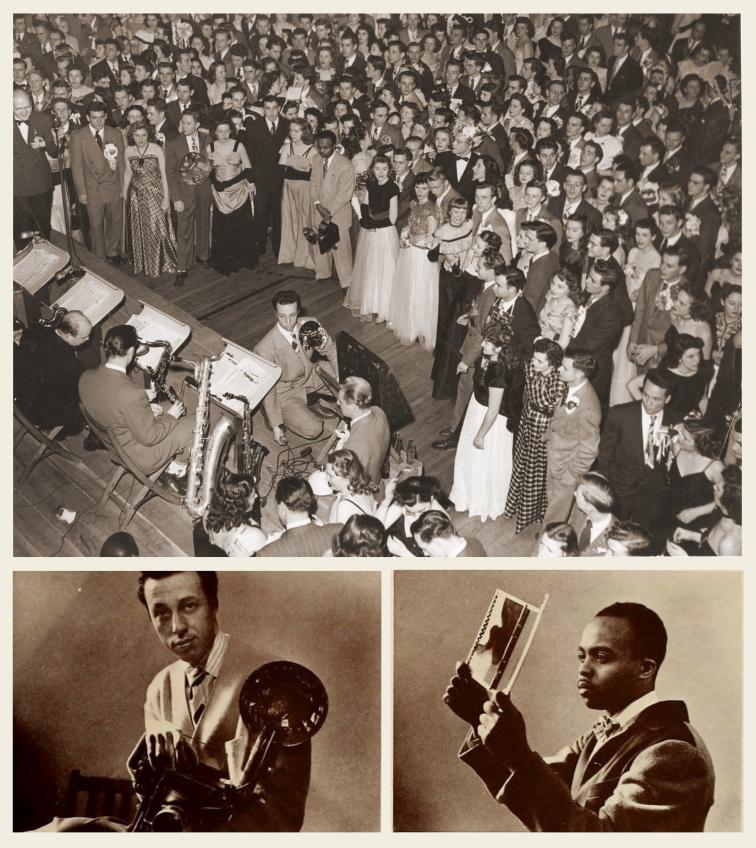

Working at the university yearbook as a photographer and darkroom manager placed Stewart alongside another young photographer in training, Herman Leonard, two years his senior. Both men captured on-campus events, portraits, and social gatherings, and both stood at the precipice of what would become intertwined photographic careers that documented and defined the cultural phenomenon of jazz music.

A visiting lecturer of photography at the time, Gerda Peterich would become the head of the photography program until 1950. She was known for her focus on photographing dance performances and dancers. Quoted as saying "photographs [function by] showing the otherwise unseen... the intimate detail that our eyes would pass over otherwise." Peterich voiced a common concern of photographic arts, one Stewart certainly considered while framing his own work. Both Stewart and Herman assisted master portraitist Yousuf Karsch for a number of years, providing lighting and camera setup for portrait sessions with some of the world's most famous personalities of the 1950s.

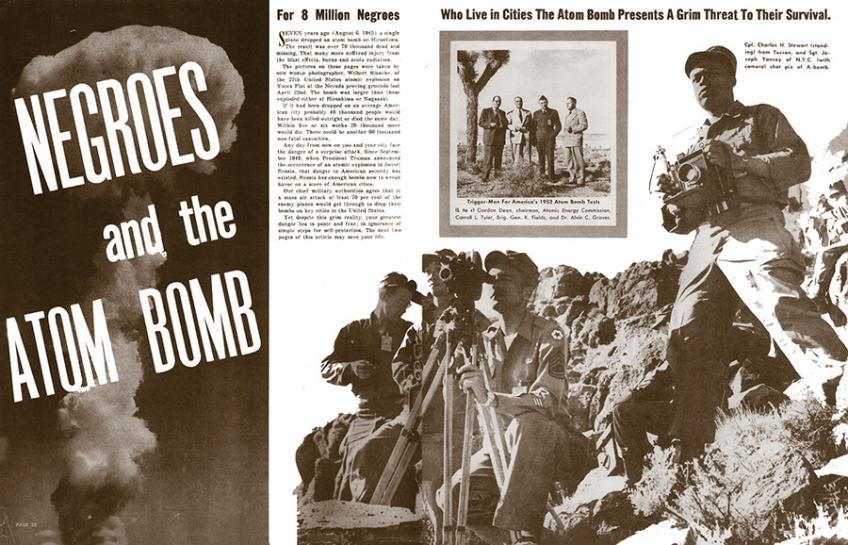

After graduating, Stewart served a few years in the United States Army as a combat photographer, which he quickly decided was not his calling. While in uniform, Stewart’s commanders recognized his photographic talents, and he was assigned to a special unit documenting atomic bomb tests in Nevada. By his account, he was the first African American to photograph these historic moments.

Upon his return to civilian life, Stewart began doing travel, fashion and advertising photography work before eventually joining his old classmate Leonard at his Manhattan studio, where the two began working with recording companies and musicians together. Stewart was also a film developer and printer for Life magazine for a period of time in the early '50s as well.

Stewart developed a lifelong friendship with Leonard during their years at OHIO and working together afterwards. In an unpublished interview with writer/producer Nikhil Bhardwaj, Stewart recalled that “he inspired me as a photographer. Most of the things I learned about photography, about how to take a picture, I learned from [Leonard], and being exposed to [him] and Karsch, I learned what goes into taking a picture.”

“A camera is a tool for me," said Stewart. "I don’t use a camera to take a picture, the picture is in my mind and I just wait for the decisive moment.”

Kim Stewart, Stewart’s daughter-in-law and representative of the Chuck Stewart Estate, said“He often boiled his approach down to carefully photographing his subjects in a manner that he thought they looked best. As a testament to this, his photographs were often best-known by the musicians themselves, who would sometimes demand that Stewart shoot their record cover [photographs] during contract negotiations.”

This drive to make his subjects look good, paired with the access the camera afforded him, opened doors for Stewart to recording studios, live venues, and backstage access on tour with some of the greatest living musicians of his time. With his camera, Stewart had the power to influence the way in which his subjects held themselves, and he had the means to represent their public personas. Developing these relationships directly with the artists was the surest route to making a living, especially for Stewart, who was attempting to work in an industry in which black photographers were often overlooked, and even intentionally shut out.

“I would be a millionaire if I was allowed to do what I was trained to do, but advertising agencies wouldn’t hire black photographers,” recalled Stewart in his conversations with Bhardwaj.

“Chuck never brought his work home, never talked about it with his friends and family, unless you were in the music industry you probably didn’t know who he was. His neighbors for decades didn’t know of the list of celebrities he photographed, or the jazz greats he spent time working with,” Kim Stewart recalled.

Although he often gets labeled as a jazz photographer, he also covered legends of rock music like the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin among many others. According to his estate, Stewart also photographed celebrated sports figures like Jackie Robinson, Arthur Ash, Mike Tyson, and Lou Rawls, as well as notable public figures like Albert Einstein. The National Endowment for the Arts, the Smithsonian, and the National Portrait Museum all have Stewart's work in their permanent collections.

In 2016, Stewart donated a selection of 25 photographic prints documenting the legendary jazz saxophonist and composer John Coltrane’s 1964 recording sessions for his album A Love Supreme to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The prints relate directly to the Smithsonian’s prior acquisition of the manuscript for one of Coltrane’s best known compositions, and although some of Stewart's images had been published previously, the bulk were being seen for the first time by historians, jazz fans, and audiences with an interest in photographic history. The photographs include Coltrane's wife, Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Rashied Ali, and Jimmy Garrison.

David Haberstich, Curator of Photography at the Archives Center of the Smithsonian Museum of American History, said, “Because of the strong American music program at our museum, photographs of jazz musicians happen to be one of our specialties. These new prints were made especially for us. Chuck Stewart was one of the premier jazz photographers, along with other luminaries such as Bill Claxton, Francis Wolff, and Herman Leonard (whose photographs we have collected as well), although [Stewart] didn’t restrict himself to that field [alone].”

In a 2015 Newsweek video profile How Best They Looked To Me, Stewart said, “I was trained as a photographer. I just happened to do a lot of work for record companies. In America everybody needs to be labeled. So as far as people are concerned I’m a jazz photographer. But what does that have to do with anything, because I’ve also photographed Bo Diddley and Leopold Tchaikovsky.”

Over the last few years a larger public recognition of Stewart’s work has begun to take shape, and his work has been highlighted by articles in the New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, and NPR among others. His images continue to support the telling of the story of jazz music through inclusion in films such as Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary (directed by filmmaker John Scheinfeld, 2017), Maya Angelou—And Still I Rise (PBS American Masters documentary, 2017), and James Brown—Mr Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown (HBO Films 2014, produced by Mick Jagger and filmmaker Alex Gibney).

In 1965 he moved to Teaneck, New Jersey, where he and his wife would raise their family of three children, and remain. Although New Jersey became home base, he continued to travel and photograph all over the country.

Stewart claimed an archive of nearly a million images, captured over 70 years, in a 2015 article in Newsweek. He documented some of the most well known and highly respected artists in the music industry, in addition to celebrities far and wide. Trying to wrap one's mind around all of what Stewart's images might contain is humbling; there are many images yet to be published. In a world hungry for new perspectives, we can only guess just what Stewart's full archives might contain.

This accomplished College of Fine Arts alumnus passed away on January 20 in his hometown of Teaneck, survived by three adult children, seven grandchildren, and one great-granddaughter. Stewart would have turned 90 in 2017.