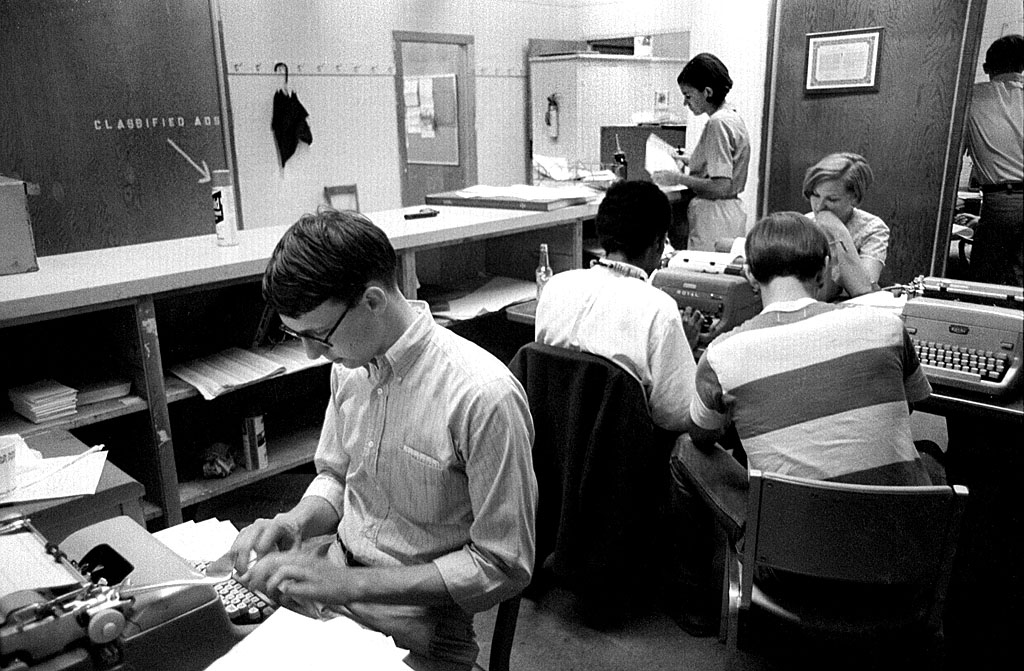

Pictured inside the composing room of The Athens Messenger are staff members from the 1967-68 Post, including [THIRD ROW, FROM LEFT] Mark Roth, Andy Alexander and Tom Hodson, [SECOND ROW, THIRD FROM RIGHT] Carol Towarnicky, and [FRONT ROW, FROM LEFT] Clarence Page and Ken Steinhoff, who served as The Post’s photo editor. © Ken Steinhoff – All Rights Reserved.

In 1969, four young Ohio University journalists were contributing editors at The Post: Andrew Alexander, Clarence Page, Mark Roth and Carol Towarnicky.

Over the next half century, all four of these “Posties” built on their experiences at the University to survive and thrive in the newspaper industry. Alexander went on to become the head of the Cox Newspapers Washington bureau, then worked as ombudsman at The Washington Post and now is a visiting professional at Ohio University. Page became a columnist for The Chicago Tribune, where he still works, and in 1989, won the Pulitzer Prize in commentary. Roth spent the last 33 years of his career with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and served as the newspaper’s founding science editor. Towarnicky became a columnist and editorial writer for The Philadelphia Daily News and co-wrote a series on Philadelphia’s decrepit city parks that was a Pulitzer finalist in 2002.

In this issue of Ohio Today, the four seasoned journalists reflect on how the University shaped their careers, the major changes they have witnessed in the news industry, and their concerns and hopes for the future.

How did Ohio University shape your career?

Towarnicky, AB ’69: I wasn’t a journalism major, and so I actually got my journalism education from the people at The Post, who taught me how to write news stories and edit. As a contributing editor, I was able to write a weekly column and it did sort of give me my first opportunity to write opinion journalism, which has been most of my career. There also were a lot of women, relatively speaking, at The Post, and when it came time to look for work, Ohio U’s reputation meant we were able to go forth and get job offers in the newsroom, where most jobs for women at the time were still in the women’s department.

Alexander, BSJ ’72: It was a tumultuous time in the 60s because you had Vietnam and the civil rights movement and the women’s movement, and I think we were very comfortable questioning authority. As young journalists, we were very confident in asking questions, and I just think we believed we could succeed as journalists.

Page, BSJ ’69, HON ’93: I’m happy about the kind of journalism education I got at Ohio University on two levels; one, in the journalism classroom, and then at The Post and other media on the campus. The advantage of a big university is there’s a lot of different people involved in a lot of different things, and we all know that the late 60s was a time where a lot of different things were going on. I graduated in one of the last years when you had a real demand for bright young people to apply for newspaper jobs, and I had about four or five different job offers. I decided I wanted to go to a big city, and that was The Chicago Tribune, and I just celebrated my 50th anniversary there.

Roth, BSJ ’69: I think more than anyone else in this group I was a total blank tablet when I came to The Post. I was on a branch campus the first two years. And when I walked into The Post office, I had no idea what was required and asked if I had to bring my own typewriter. I learned everything from my fellow student journalists, and it really taught me the basics of the profession. I can’t imagine a better training ground.

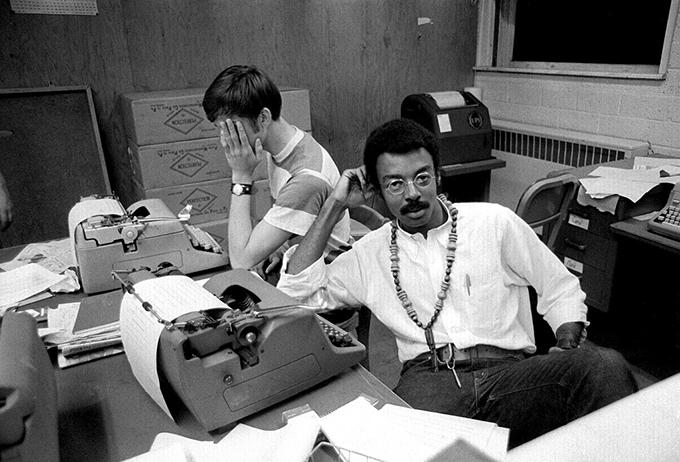

[FROM LEFT] Mark Roth, BSJ ’69, and Clarence Page, BSJ ’69, work in the office at The Post, Ohio University’s student-run newspaper. © Ken Steinhoff – All Rights Reserved.

What changes have you seen in the news business, and do you have hope for the future?

Alexander: One tumultuous change in the news media is that we don’t have the money we used to have. I can remember an era when The Atlanta Journal-Constitution had so much advertising that the presses were literally running 24 hours a day. The internet upended that and so these are very challenging times. I’m concerned about the demise of local news. We have a spread of news deserts where local newspapers have gone out of business. When that happens, studies have shown voter participation drops, fewer people run for office, and there is more malfeasance, simply because there is not a news organization holding people to account. On the positive side, I’m a visiting professional at Ohio University, and in the upper tier of our journalism school, you find students who not only understand how to do quality journalism but why it’s important.

Page: At The Chicago Tribune we have virtually closed our Washington bureau to focus on local news. So many owners now are some kind of holding company buying newspapers as an investment and raking off the profits and moving on. On the other hand, not only are young journalists out there today, but they are just as crazy as we were and they’re bringing to the business a new energy.

Towarnicky: On the editorial pages, what I thought was the most important job a newspaper did was to interview local candidates for endorsements and do more research on them than people could do on their own. That’s disappearing due to cuts in staff and time. On the hopeful side, the internet has given us access to enormous amounts of detail and information if we use it correctly.

Roth: This may sound selfish, but newspapers were usually the first news organizations to find things out, and we all know that the other people who have made a lot of money off our backs could not have done that without newspapers telling them what it was they were supposed to be interested in in the first place, and I see that starting to disappear. On the positive side, I still get to teach really bright, inquisitive students who want to go into journalism, and I think the real challenge is how they’re going to make a decent living doing that.

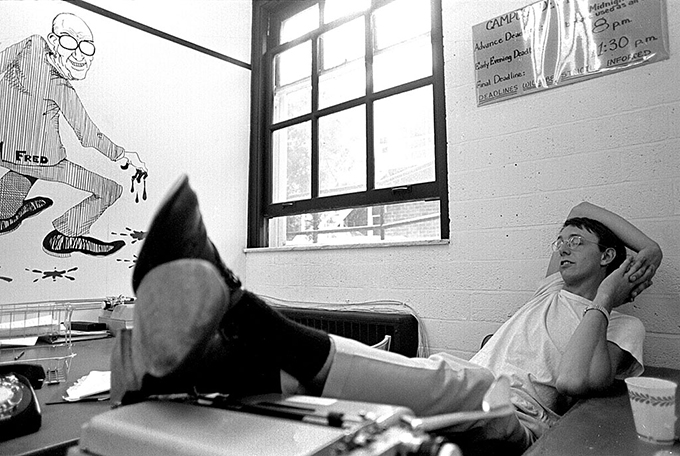

Andy Alexander, BSJ ’72, was a contributing editor at The Post and today serves as a visiting professional at OHIO’s Scripps College of Communication. © Ken Steinhoff – All Rights Reserved.

Staff members from The Post watch as the first edition of the newspaper for the 1968-69 academic year rolls off the presses at The Athens Messenger. © Ken Steinhoff – All Rights Reserved.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the news industry?

Alexander: COVID-19 has accelerated the decline of the news industry. In April and May alone, 30 newspapers were forced to close or merge because of lost advertising revenue due to the economic meltdown. For many outlets, the financial situation is dire. But COVID has produced two bright spots. First, readership of local news has never been higher because citizens are hungry for reporting that helps their communities survive and thrive. Second, the pandemic has forced many local news outlets to experiment with new ways to monetize this reader loyalty. It’s very much a race against time. Can local news providers adopt new and sustainable business models before the economic devastation from COVID forces them to close?

Page: For me, the biggest change is that I haven’t seen my office or colleagues, except by Skype or Zoom, since the pandemic began. This has shattered the last vestiges of newsroom culture as I used to know it. So has the closing of saloons, fitness centers, pro sports and other hangouts that put me less than six feet from whomever I was talking to. On the other hand, I save so much time, money and temper by telecommuting that I may never go back to buses, taxis, trains and parking garages. Sources seem more eager to talk after they, too, have been cooped up alone for days. And remember that old New Yorker cartoon about the dog and a computer? “On the Internet,” the caption read, “no one has to know you’re a dog.” I have a new version: “In your home office, nobody has to know you’re taking a nap.”

Towarnicky: Newspapers traditionally are the “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to economic downturns since the first thing businesses tend to cut is advertising. The print version of the newspaper in Philadelphia sometimes has only one section – no separate fronts for local news or sports. And the way COVID has upended our lives probably also has upended the traditional ways newspaper departments have been organized. With the suspension of the basketball, hockey and baseball season last spring, the sports section abruptly lost the bulk of its subject matter. There was no local theater to review, feature films were delayed or streamed on television, and coverage of the lively restaurant scene was relegated to news of which locations had temporarily closed or gone out of business permanently. If our lives ever return to a semblance of the way they were, it’s unlikely newspapers will. Except for sports, there likely won’t be much room again for local takes on many of these “soft” subjects

Roth: As a news consumer, I have found myself reading a larger array of newspapers – and gratefully paying for the privilege. I added The Minneapolis Star Tribune after George Floyd’s death, and I added The Houston Chronicle because it has been a COVID and political hotspot. In the meantime, though, my local newspaper continues to lose its best people through buyouts and layoffs, so I worry that the industry I dedicated my life to may crumble before my eyes, at least at the regional level. The New York Times and Washington Post will be fine, but what about Milwaukee and Baltimore and St. Louis and Kansas City and all the midsize cities that have proud newspaper traditions? This is where we need innovative economic solutions, and we need them fast.

Feature image: Staff at The Post had their work cut out for them in 1969, covering everything from the Vietnam War to the civil rights and women’s rights movements. © Ken Steinhoff – All Rights Reserved.