Nearly 13,000 years ago, people journeyed more than 300 miles to what is now central Pennsylvania, leaving traces of their lives at the Shoop Paleo-Indian site. Among the earliest documented Paleo-Indian sites in eastern North America, the site holds clusters of artifacts that may represent family groups or repeated visits over generations.

The Shoop site has long been central to archaeological research, offering continent-wide evidence of how some of the first people in North America migrated. Today, the legacy continues as Ohio University students join faculty and volunteers in uncovering new layers of the site. Through excavation and analysis, they are adding fresh ideas to a story thousands of years in the making, while gaining hands-on experience that brings their studies to life.

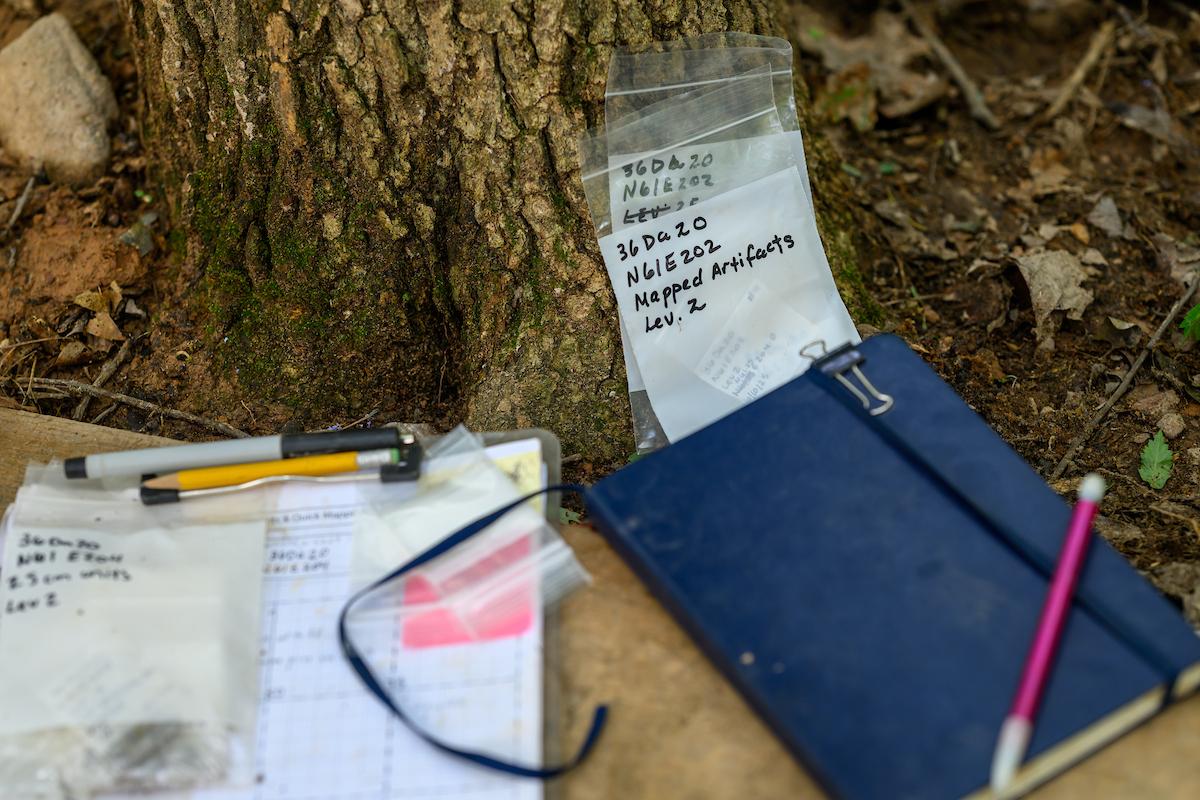

History in hand

For nearly 40 years, students from Ohio University have been digging through the Ohio Archaeology Field School, gaining real-word experience in uncovering the past. From anthropology majors to English majors, hundreds of students have participated in the program and learned from working on sites like Shoop. The field school provides training that prepares students for many careers related to archaeology.

Set in remote Halifax, Pennsylvania, this summer's four-week long field school program had students living fully immersed in archaeology. They camp on-site, prepare their own meals and rotate through nightly cooking duty, routines that build independence and a sense of community.

Digging into student life

Students began their fieldwork at Wayne National Forest before continuing on to the Shoop Paleo-Indian site in Halifax. United by their shared passion for uncovering the lives of people who walked on the land thousands of years ago, they quickly formed close connections through their work. Living, learning and digging side-by-side, the students gained valuable archaeological skills while transforming from classmates to teammates, and then into friends.

Tony Chicatelli

For Chicatelli, a senior majoring in linguistics with an anthropology minor, archaeology added depth to his study of endangered languages. He said the dig connected the languages he studies to the people who once spoke them. After taking Joe Gingerich’s archaeology class, he jokes his mind was “poisoned” into pursuing fieldwork.

“I like the whole atmosphere … the relationships among the students and with our professor,” he said. "The whole site's really interesting."

Rachael Culver

For Culver, a senior history and English double major, field school blended her love for her two majors. She said the demanding four weeks challenged her but also provided rewarding growth. Beyond learning archaeological skills, Culver said she treasures the friendships formed during the dig, bonds she knows will last long after the experience.

“I don't know how tight people in past field groups have been, but I feel like this one … we're all going to be hanging out again,” she said.

Maddy Feerick

Field school brought junior anthropology major Feerick’s anthropology studies to life, turning classroom concepts into solid discoveries. Even finding fragments of artifacts sparked excitement, making archaeology feel magical. She said the hands-on work strengthened her passion for the field and inspired her goal of pursuing museum studies to share history with others.

“I'm really excited about the skills that I'm learning, and what kind of opportunities are going to be opened up for me because of that,” she said.

Kira Rossi

Sophomore anthropology major Rossi’s childhood interest in paleontology evolved into a passion for archaeology, solidified during field school. Excavation skills and hands-on discoveries confirmed her desire to pursue graduate studies in archaeology or paleoanthropology.

“I've met a lot of really wonderful people, and I'm really happy to have been able to spend time with them,” she said.

Jared Shell

Originally outside anthropology, Shell, now a senior anthropology major, joined field school for the chance to experience archaeology firsthand. The dig introduced him to a community of peers sharing his fascination with cultural diversity. He also formed lasting friendships while exploring a field that became his passion.

“I met a lot of good people that I am now friends with, and will stay friends with long after the field school,” he said.

Audrey Tompkins

Tompkins, a senior anthropology major, started in sociology but was drawn into anthropology by inspiring professors like Gingerich. Though archaeology wasn’t her initial focus, field school shifted her perspective, helping her discover unexpected passion, build friendships and see real-world applications of her studies.

“Archaeology wasn't really on my radar of something I was thinking of doing, and [field school] totally changed my mind,” she said.

One thing that I remember from my field school when I was young is that I made lifelong friends, and I’m hearing the same from these students.

Guides in the dig

At the heart of the field school is Joe Gingerich, Ph.D., and Kurt Carr, Ph.D., retired curator of the State Museum of Pennsylvania. Combined they have more than 85 years of field experience. Carr celebrated 60 years in the field this summer and has worked on the Shoop site since the 1990s; he invited the field school to visit the site and was eager to share his decades of knowledge with its students. Gingerich and Carr have guided both the program and the students’ experiences and spent most of their careers studying early human migrations across North America, with the Shoop site offering a unique look into those stories.

For Gingerich, the field school is about more than research; it's about mentorship and building connections. By guiding students through hands-on work and encouraging teamwork, he turns the dig into a classroom without walls, where curiosity, collaboration and discovery go hand in hand.

"One thing that I remember from my field school when I was young is that I made lifelong friends, and I’m hearing the same from these students," he said.

Alongside the students and faculty, volunteers play an important role in the success of the field school. Community members, alumni and enthusiasts bring extra hands and fresh ideas to the excavation, helping keep the dig moving forward. Their participation not only supports the research but also builds bridges between the University and the archaeology community. For students, working alongside volunteers shows that archaeology is more than an academic pursuit; it's a shared passion that welcomes people from many different backgrounds.