Ohio University researchers find bobcat population rising, with room for growth

Ohio University researchers report that bobcats – Lynx rufus, the furry, spotty felines, not the OHIO students – are expanding across the state and have adequate habitat to continue rebounding.

Researchers led by Viorel Popescu, Ph.D., have been studying the ecology and threats to the bobcat population over the past four years. Their overarching goal is to evaluate the status and viability of Ohio’s bobcat population.

As part of this Ohio Department of Natural Resources-funded study, new research recently published in the open-access journal PeerJ investigates how bobcats use habitats and habitat connectivity – how the landscape helps or hinders the bobcats’ movement – and whether that would allow them to continue expanding across Ohio.

This study involved graduate and undergraduate students from the biological sciences department in the College of Arts and Sciences and the Honors Tutorial College as well as collaborators with the Ohio Division of Wildlife and Ohio State University. The researchers used a long-term dataset of bobcat observations (2000-2019) by Ohio residents and collated by the Ohio Division of Wildlife to evaluate selection of habitats across Ohio and to predict habitat suitability for harboring bobcat populations.

Southeastern Ohio remains stronghold for bobcats

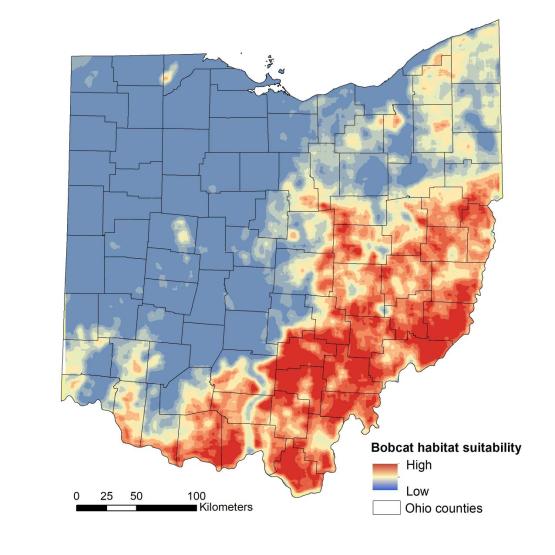

Ohio University researchers found that habitat suitability was associated with higher cover of forest and open natural habitat and was not influenced by the presence of high-traffic roads. They also found that habitat connectivity for movements was high, including in most of the agricultural areas of Ohio, thus there is still potential for bobcat expansion in Ohio.

“Southeastern Ohio, with its significant forest cover, remains the stronghold for bobcats in Ohio,” said Popescu, associate professor of biological sciences and lead PI on the project. “In addition to the hundreds of sightings over the past couple decades, there are many signs that lead us to believe that the population continues to expand throughout Ohio.”

Bobcats are shy animals and not a usual sight for most people, and they are able to thrive in human-dominated landscapes such as southeastern Ohio. As such, roads did not have an effect on habitat use by bobcats, despite being the main source of mortality for Ohio bobcats, he added.

The researchers found that while forested southeastern Ohio is the most suitable area for bobcats in the state, southwestern and northeastern parts also can support bobcats. These areas have pastures and other natural open habitats that bobcats use for foraging to target small mammals and hares.

The one area where the models predicted low or no suitability is central Ohio, which is dominated by heavy agriculture and lacks natural habitats that bobcats can use.

Using citizen-collected data is not without its pitfalls, though, says a student who analyzed the data.

“We found that the number of bobcat sightings increased significantly in Ohio, especially since 2010, but is this a real or an artificial increase? There is definitely a bias in the number of sightings here because in recent years camera traps have become affordable, and many people have cameras in their backyards and report bobcats,” said Madeline Kenyon, a senior Honors Tutorial College student with a focus on wildlife conservation.

However, many sightings since 2015 occurred in areas where bobcats have not been previously documented, suggesting that bobcats do indeed continue to expand in Ohio, the researchers noted.

River valleys helped bobcats disperse across state

“Suitability of habitat is not everything, though. We need to understand how animals move across the landscape and identify corridors for natural dispersal,” said Marisa Dyck, a doctoral student in Popescu’s lab.

The Ohio bobcat population is part of the larger Midwest population, which was the source of animals that founded the current Ohio population. Bobcats were extirpated from Ohio by the mid-19th century but started to come back to the state a century later in the 1960s-70s.

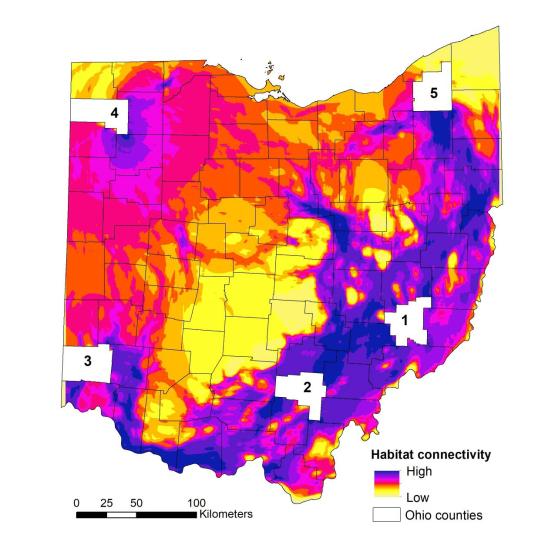

Tracking that rebound means that identifying and mapping areas of high and low connectivity, along with so-called “pinch-points,” or narrow corridors that allow dispersal within inhospitable habitat, can be critical for management decisions to maintain a viable population. The researchers used habitat suitability maps to build connectivity maps between core and peripheral areas of Ohio.

“The habitat connectivity findings were very interesting,” Dyck said. “We expected that eastern and southern Ohio would be well-connected and facilitate movements of animals, but we also found conduits for movement and dispersal in central, agricultural Ohio. These corridors of river valleys with forest cover in their immediate proximity connected the source populations in southeastern Ohio to less suitable areas. The Ohio River Valley was also important for bobcat movements, especially in the southwestern part of Ohio, where we found a pinch-point in Brown and Clermont counties.”

One of the unique features of this study was that researchers were able to validate their connectivity findings with sightings of dispersing bobcats in central Ohio.

“In summary, bobcats may be habitat-limited in the agricultural region of Ohio, but zones of high connectivity across Ohio results in the ongoing expansion across the state and maintaining connectivity between the Ohio population and other Midwest states,” Popescu said. “We are now working with Ohio Division of Wildlife biologists to develop a model aimed at supporting bobcat management decisions and ensuring that these beloved felines have a certain future in Ohio for years to come.”