Joseph Gingerich, Ph.D., an associate professor of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences at Ohio University, and his students recently had the chance to take part in a rare experience for undergraduate students. A select group of professors, students and alumni traveled to Virginia's Roanoke River Valley to take part in an archaeological dig on a 13,000-year-old site from Nov. 4-13.

The site provides some of the oldest evidence of human activity in the Eastern United States, but due to erosion and fluctuating water levels in the area, some of that activity can be difficult to document. Gingerich said that the erosion is a mixed blessing.

"Erosion has alerted us to their presence, but it's a difficult situation as these sites are being lost so fast," Gingerich said. "Our goal is to locate areas that are still preserved, so we can understand more about past lifeways." Gingerich started working on these sites five years ago with funding from National Geographic and additional research grants that he received provide opportunities for students.

Working on this site provides a rare and valuable opportunity for undergraduate students still honing their skills. "Many of the students are using advanced mapping techniques and advanced collection techniques. So, it provides unique training and skill sets for students moving forward," Gingerich said.

In 2017, the College of Arts and Sciences renovated a new state-of-the-art lab space for the anthropology and archaeology program. Gingerich noted that students are not only gaining field experience but important lab skills that will aid them in careers in archaeology and museum studies.

Archaeological Society of Virginia volunteers work along with students on excavations.

Archaeological Society of Virginia (ASV) volunteers work along with students on excavations.

"Students get to see the entire process, how artifacts are collected in the field and then processed and analyzed in the lab," Gingerich said. The grants that fund the Virginia work will also be used to pay students in the lab. Many of the students who took part in the dig had just participated in the Field School in Ohio Archaeology, which provides basic training for archaeology, but according to Gingerich, the Virginia dig was a chance to gain a broader and deeper understanding of the work.

One of these students is Tori Lovelace, a sophomore studying anthropology with a focus in archaeology in the Honors Tutorial College. Lovelace said she did not expect an opportunity quite like this so early in her undergraduate career. "I expected to do some (local) digs, but I did not expect to be invited on a trip to Virginia to dig a 13,000-year-old site. Not many people in archaeology get to do that, much less an undergraduate student," Lovelace said.

When it comes to the work that was done in Virginia, Gingerich said the main goal of the work is to capture the different sites before they're lost to erosion.

Dr. Joseph Gingerich teaches student Hunter Arnett how to map artifacts.

Students water screen to recover small fragments of stone tool manufacturing.

Archaeological Society of Virginia volunteers work alongside Ohio University students on an excavation site in Virginia.

Students work to precisely map the location of experimentally produce stone tools to examine erosional processes in the river valley.

Student Deontae Brown excavates a unit.

Students and Volunteers carry equipment to excavation areas.

Students and volunteers carry equipment to excavation areas.

"Frankly, most of these sites have eroded out. In some ways it's good, but at the same time it's been difficult to document these last few sites before they're gone," Gingerich said. "It's been an opportunity to save something that in the next few years will be absolutely gone."

Once these sites are lost, researchers will know less about the earliest human activity throughout this region of America. However, the nature of the sites does not mean there were no opportunities to unearth ancient artifacts.

Lovelace explained that the majority of the objects found are small remnants of making and re-sharpening stone tools, but some of the materials unearthed were fascinating.

"A lot of what we found were clear quartz flakes, and they were gorgeous," Lovelace said. "Those were really memorable because I had never seen material like that and we really don't have anything like that in this area."

Gingerich noted that these early people used very high-quality stone to make stone tools. Some of the materials used come from hundreds of miles away.

Student Tori Lovelace excavates on 12,000 year old surface.

Student Nellie Sullivan finishes screening for artifacts at the end of the day.

Dr. Cory Crawford (Right) from the Classics Department works with student Cassady Wallace.

Dr. Gingerich examine artifacts with ASV members Bill Childress and Jeanette Cole. Childress and Cole have extensively work to map and report sites throughout this portion of the Roanoke River valley.

Gingerich examines at Late Prehistoric Yadkin style point made out of high quality raw material.

Crew shot from the 2021 Field Session which includes two Ohio University alum, four ohio ASV volunteers and the State Archaeologist of VA.

Dr. Gingerich uses a total station to map artifacts with sub-centimeter accuracy

Book shelf at the archaeology lab at Ohio University.

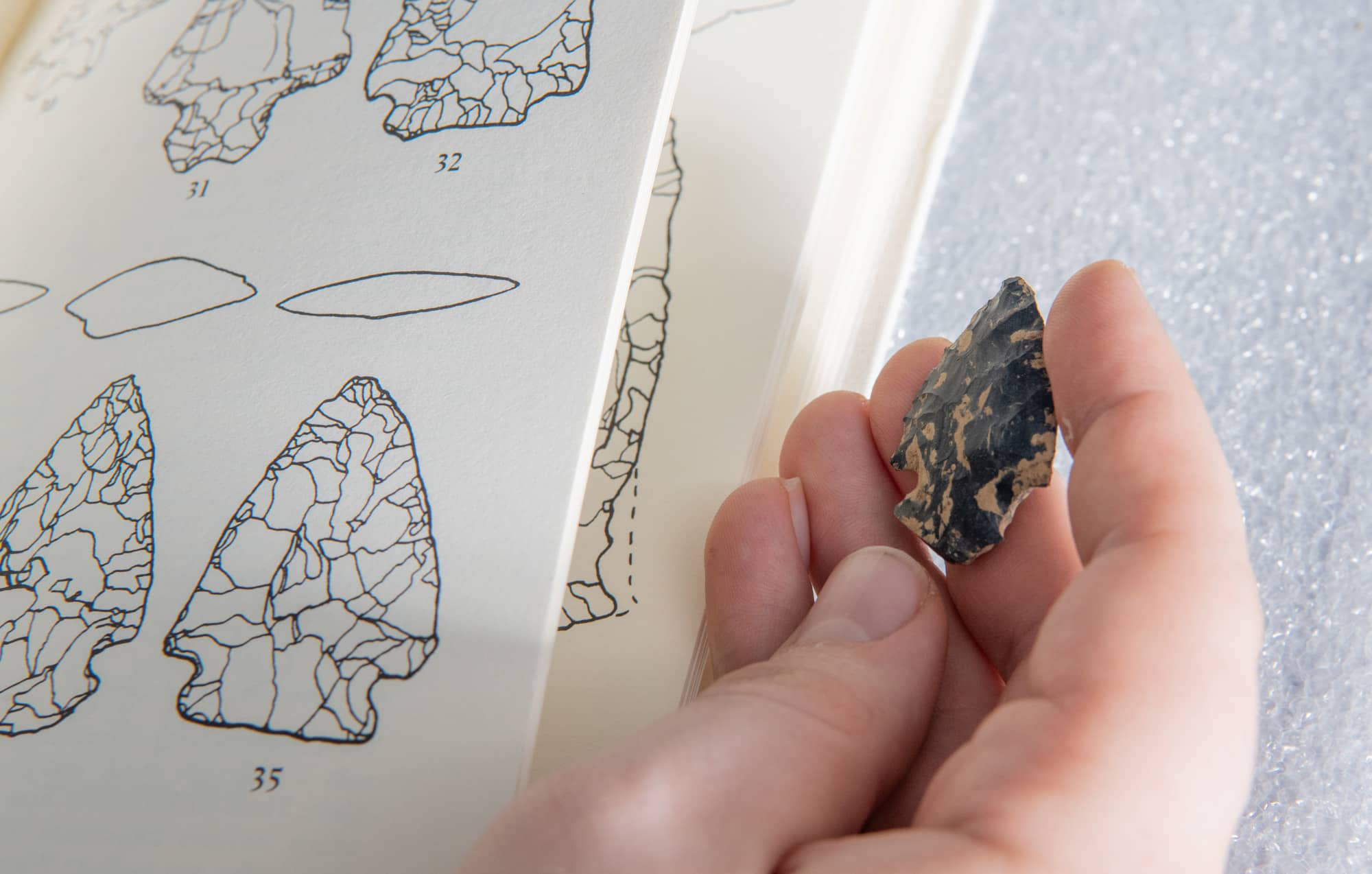

Ohio University student and now alum Jacob Carlson, attempts to identify an arrowhead found by Archaeology Field School students in the Anthropology Lab.

Ohio University student and now alumnus Jacob Carlson attempts to identify an arrowhead found by Archaeology Field School students in the Anthropology Lab.

Aside from the professional impact this work has on students in the program, it's an opportunity unlike anything Ohio University students have had in the past. David Lamp, an alumnus of the anthropology program at Ohio University, had the chance to take part in the trip with Gingerich and his students.

Lamp believes the work Gingerich is doing, and the experience it gives his students, takes Ohio University's anthropology and archaeology programs to new heights.

"In my time at Ohio University, the anthropology program was a good program, but this is not an opportunity I had as an undergraduate," Lamp said. "Dr. Gingerich is a good person to take the program where it needs to go, and opportunities like this truly elevate Ohio University."

Dr. Joe Gingerich in his lab at Ohio University.

Ohio University student and now alum Jacob Carlson, who also participated in this years dig gained extensive experience in prehistoric artifacts through work in the Anthropology Lab.

Alum and now archaeology Master's Student at Mississippi State completed a number of research projects using collections stored in the lab. Including artifacts from the excavations in Virginia.