John Kopchick, Ph.D., hasn’t discovered the fountain of youth, but he has discovered a key hormone inhibitor—one of the blockbusters of the pharmaceutical industry—that affects aging, diabetes and cancer.

Kopchick came to Athens in 1987, lured from a position with pharmaceutical giant Merck by an offer to become one of Ohio’s first eminent scholars—an endowed professorship funded by the state and OHIO alumni Milton Goll, AB ’35, and Lawrence Goll, BBA ’66—and an opportunity to work at the Edison Biotechnology Institute.

The institute had one of the few labs in the world capable of producing transgenic animals, whereby cloned genes are transferred from the laboratory to mice through DNA microinjections. It was a revolutionary breakthrough in biomedical research discovered by an OHIO research group led by Professor Thomas Wagner, who in 1981 made global headlines after successfully producing the world’s first transgenic mouse and patenting the technology behind it.

Using transgenic mice, Kopchick began experimenting with growth hormone, a protein that captured his attention because of its ability to dissolve fat while increasing muscle and bone mass, but that also is associated with an elevated risk of diabetes and cancer.

“We started out saying, let’s see if we could change the growth hormone molecule in specific places and retain the good things—the ability to make bones grow, decrease fat, build muscle—and do away with any of the bad actions,” said Kopchick, now a distinguished professor in the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s Department of Biomedical Sciences.

Kopchick and the graduate students in his lab began altering each of the protein’s 191 amino acids. The team screened the effects of each alteration by injecting the modified genes into mice, hoping to get a larger mouse resistant to diabetes and cancer. One change made by student Wen Chen, MS ’87, PHD ’91, brought the unexpected: a dwarf or “mini-mouse.”

“I didn’t believe it, so I had the student go back and repeat the whole thing,” Kopchick said. “Sure enough, he was getting these small animals. One amino acid change out of 191 made it a growth hormone receptor antagonist.”

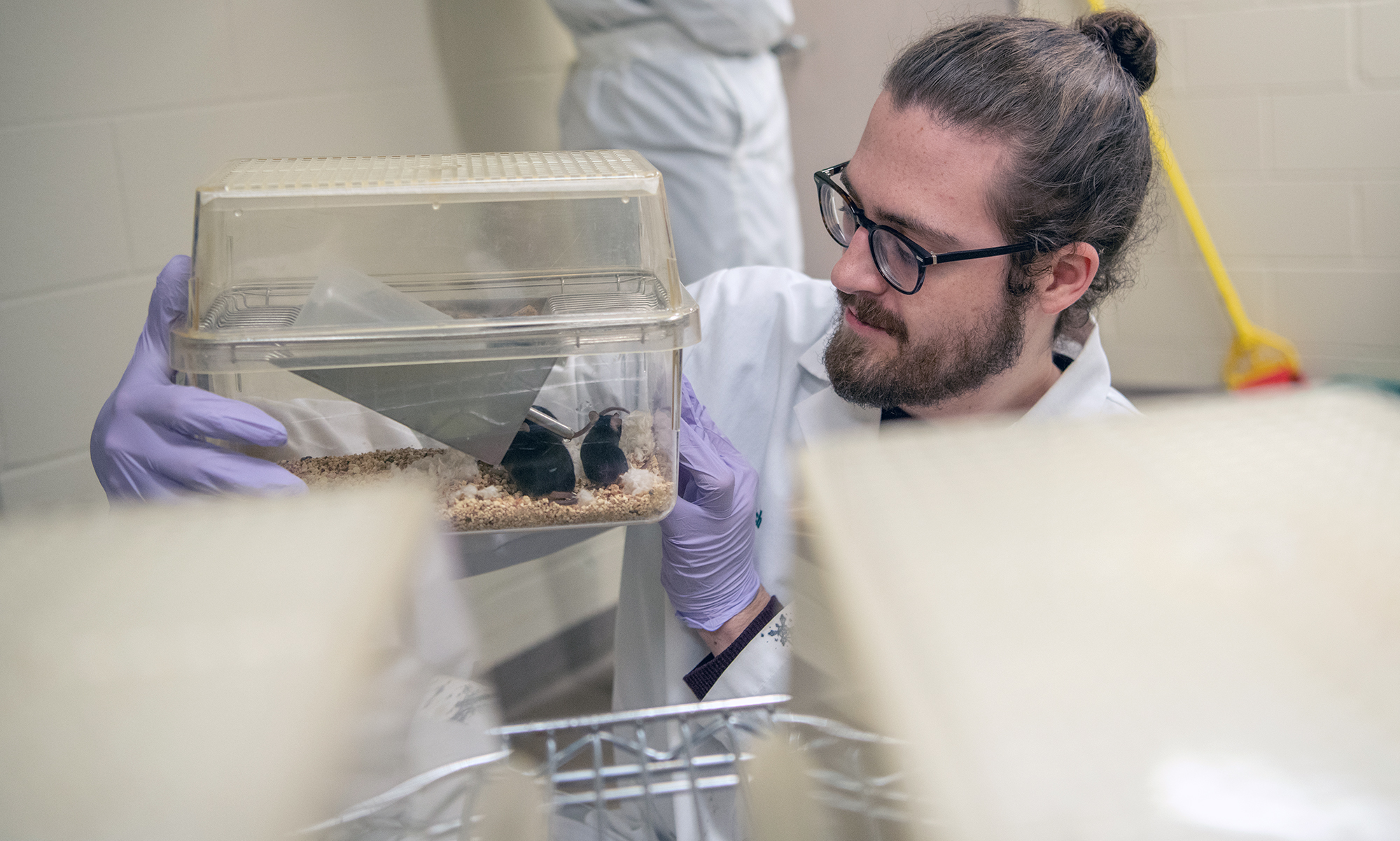

John Kopchick works with graduate students to study the effects of the growth hormone antagonist he discovered. Photo by Ben Wirtz Siegel, BSVC ’02

Kopchick knew they had stumbled onto something big—a growth hormone inhibitor. Some of the blockbusters of the pharmaceutical industry are inhibitors. Thus, working with OHIO’s Technology Transfer Office, they applied for and received several patents on the discovery.

This discovery was the first-ever large molecule antagonist, which, in its early stages of development, caused some apprehension among those in the pharmaceutical and scientific communities. But serendipity led Kopchick to Rick Hawkins, BSED ’75, an OHIO alumnus and changemaker in the field of drug development.

This dynamic duo would spend the next decade turning Kopchick’s discovery into pegvisomant, known by its brand name Somavert®, a drug used worldwide to treat a rare and life-shortening disease called acromegaly.

During this time period, another portion of Kopchick’s lab was working on attempts to remove growth hormone action in mice. If successful, those mice would be resistant to cancer and diabetes.

Graduate student Yihua Zhou, PHD ’96, took on the project and generated this mouse. And sure enough, it was resistant to cancer and diabetes and had an unexpectedly long life, as well. That mouse now holds the record as the longest-lived laboratory mouse, surviving to just one week shy of five years—double the lifespan of the lab’s control mice.

“Interestingly, humans with the same gene alteration as found in these mice have no cancer,” Kopchick noted.

Kopchick has sent the mice all over the world to research collaborators who study aging, longevity and life span. He and his students continue to publish papers dealing with these mice—showing that stopping the activity of growth hormone in different cells of the body can improve health and increase lifespan.

This story originally appeared in The Heart of Health: Showcasing Ohio University’s Leadership in Health Education.

Feature photo by Rich-Joseph Facun, BSVC ’01