What is CTE?

CTE has garnered national attention in recent years, yet, despite growing awareness, experts caution that the science is still evolving and that misconceptions remain.

“CTE is a neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated brain trauma,” explains Dr. Melissa Anderson, an assistant professor in the College of Health Sciences and Professions and an expert in concussions. “It leads to the buildup of abnormal tau proteins in the brain, which disrupt normal function and can cause memory loss, confusion, aggression, depression, and impaired judgment.”

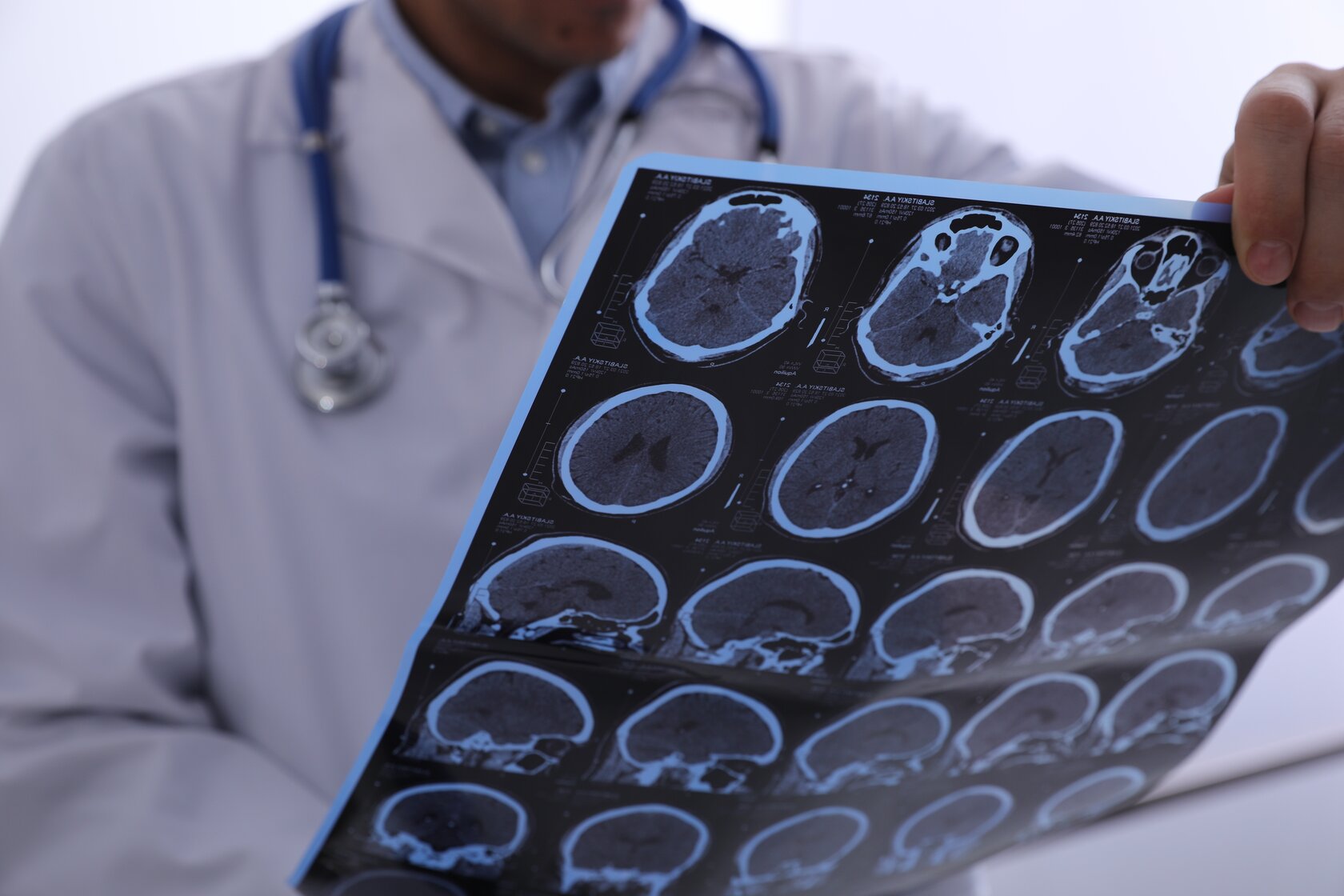

Unlike a concussion, however, CTE cannot be diagnosed in a living person. To confirm someone has suffered CTE, scientists must examine thin slices of brain tissue under a microscope to look for abnormal accumulations of tau protein deep within the folds of the brain. Anderson explained that standard neuroimaging does not detect these changes, and the symptoms of CTE often overlap with those of other neurodegenerative conditions, which makes diagnosis during life particularly challenging.

“Unfortunately, people often believe they have CTE or attribute behavior to it without any confirmation,” says Dr. Jeff Russell, an associate professor of athletic training in the College of Health Sciences and Professions who studies concussions in film and television stunt performers, among other populations. Russell’s research group also has a CTE research partnership with the Boston University CTE Center. “You can’t say someone has CTE just because they played football and have head trauma and mental health issues. That’s something only a medical professional can evaluate, and even then, CTE isn’t diagnosable until after someone passes away.”

In living individuals, doctors may instead look for signs of Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome (TES), a collection of symptoms like mood swings, memory problems and cognitive decline that may be linked to CTE. However, TES is not a definitive diagnosis, and its symptoms often overlap with conditions like depression, PTSD or even normal aging.

“Standard neuroimaging doesn’t detect the changes associated with CTE,” Anderson says. “And the symptoms can overlap with other neurodegenerative conditions, which makes diagnosis incredibly challenging while someone is alive.”

Melissa Anderson

Jeff Russell

Concussions and the invisible impact

At the root of both concussions and CTE is the mechanical trauma to the brain. A concussion occurs when a force to the head or body causes the brain to move rapidly inside the skull. This sudden movement stretches and disrupts brain cells, setting off what is called a “neurometabolic cascade,” according to Anderson.

“In simple terms, potassium rushes out of the cells and calcium floods in, creating an energy crisis in which the brain is working harder but has fewer resources available. That mismatch is what leads to the wide range of concussion symptoms, from headaches and dizziness to problems with memory or concentration,” she adds. “The important thing to remember is that there’s no single ‘impact threshold’ that guarantees a concussion. Some routine head impacts don’t cause symptoms at all, while others, even if they look mild, can trigger this cascade and result in a concussion.”

Even more deceptive are the subconcussive impacts; the small, often unnoticed blows that athletes endure repeatedly.

“Even head impacts that don’t cause a diagnosed concussion can set off changes in the brain,” Anderson explains. “They can disrupt the blood-brain barrier, alter how the brain uses energy and contribute to the buildup of abnormal proteins like tau or amyloid.”

Russell agrees, saying that the repetitive hits are often overlooked because there’s no immediate concussion. However, over a career, those smaller hits add up.

Who’s most at risk?

What makes this especially concerning is how common these impacts are in contact and collision sports. Depending on the sport and position, athletes can sustain hundreds or even thousands of head impacts in a single season.

“Research suggests that even fewer than 2,000 of these impacts across a career may be enough to raise the risk for later-life neurological problems,” Anderson says. “That’s why there’s growing attention on the role of repetitive head impacts in traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES), the clinical disorder associated with CTE. In fact, one of the proposed criteria for diagnosing TES includes a history of at least five years of organized contact sports, with at least two years played at the high school level or higher.”

Athletes in high-contact positions, like linemen, running backs, and defensive backs, face the greatest risk due to both the frequency and intensity of impacts, whereas positions like kickers and punters experience very few head impacts in comparison.

“Linemen can endure hundreds or even thousands of minor impacts in a single season,” Anderson notes. “Receivers or defensive backs may experience fewer hits overall but tend to absorb higher magnitude impacts when they do.”

Russell elaborated on the differences by position, saying, that running backs often experience fewer hits per game than linemen, but the hits they do take tend to be at full speed, with a lot of momentum behind them.

“That kind of impact can create intense trauma in an instant,” he says. “Meanwhile, linemen experience hundreds of collisions that may seem minor but affect the brain over time. It’s not just about how hard you're hit, it's about how often and under what conditions.”

The cumulative nature of head trauma is key; yet, not all athletes are affected the same way. According to Russell, two players might experience the same impact but have very different outcomes depending on genetics, injury history and recovery practices.

“It’s about understanding that every athlete is different,” Russell adds.

Younger athletes, whose brains are still developing, may also be more susceptible.

“They often take longer to recover and may be more vulnerable due to less neck strength and body mass,” says Anderson. Still, she points out, professional athletes face a much greater lifetime exposure, putting them at higher long-term risk.

The toll on mental health

The conversation around CTE often intersects with mental health, a connection both experts say is real but not always straightforward.

“What concerns me as much as the physical effects is the emotional weight of the narrative around CTE,” Anderson shares. “I once spoke with a former NFL player who described himself as feeling like a ‘ticking time bomb.’ Carrying that kind of fear can be devastating in itself. The truth is, we are still learning a great deal about the long-term effects of concussion, and while awareness is crucial, so is providing hope and support. Former athletes need to know that they are not destined for decline, and that resources, monitoring, and care can make a real difference.”

While some studies show that as few as three or more concussions may increase the risk of depression or anxiety later in life, Anderson emphasizes that mental health outcomes vary widely.

“Not every athlete with a history of concussion will experience these issues,” she says. “But the risks are real, and they highlight the importance of prevention, education and careful monitoring.”

She encourages former athletes experiencing cognitive or emotional symptoms to seek care from professionals trained in brain injury.

Ensuring safety

Both Anderson and Russell agree that the goal is not to discourage participation in football or other contact sports but to ensure that athletes, parents and coaches are prepared with accurate information.

“Informed consent is everything, no matter if it’s sports or performing arts,” Russell says. “If you want to be a stunt performer or play football, that’s your choice. But you should understand the risks and be in an environment where you are valued and where everything possible is done to keep you safe.”

That environment includes better helmet technology, stricter return-to-play protocols, real-time sideline evaluations and cultural shifts that empower participants to report symptoms without stigma.

“Culture plays a big role,” says Anderson. “We need to move past the outdated idea that toughness means hiding symptoms. The stakes are too high.”

In recent years, several NFL players have retired early, citing concerns over brain health. Others, like Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, have continued despite multiple concussions, highlighting the deeply personal nature of these decisions.

While science has yet to provide all the answers, ongoing research, innovation and awareness are helping make sports safer.

“The more we understand, the better we can protect athletes at every level,” Anderson says. “And that starts with taking the science seriously.”

Russell agrees, saying, “The goal isn’t to scare people away from football or any other activity. It’s to give them the knowledge, and the support, they need to make smart, informed choices.”